This was followed by brief beers down the road with Moo & Thea; trammage back to mine with Thea, and thence into town; a MIFF screening of Marina Abramovic: The Artist Is Present with Bousy & her friend Luke at ACMI; drinks with Bous, Luke, Kellie & Nathan in Fed Square after that, and then Adam’s Birthday, which inevitably kicked on until about midday the next day. After that I slept for 16 hours.

Category Archives: Books

Anarchist Bookfair @ Abbotsford Convent

Filed under :), Benevolence, Books, Hectickery, Movies, People, Photos

Entertaining Budini

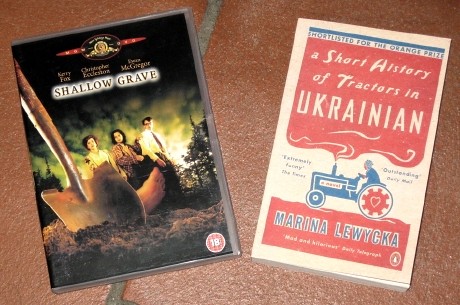

What I Got For Christmas

John Fowles Dead

Victory for the Trysting Fields campaign!

UPDATE: The post cited above just got linked by the BBC!

Filed under Books, Current Affairs, Neurocam, People, Whack

The Lottery In Babylon

by Jorge Luis Borges

LIKE all men in Babylon, I have been proconsul; like all, a slave. I have also known omnipotence, opprobrium, imprisonment. Look: the index finger on my right hand is missing. Look: through the rip in my cape you can see a vermilion tattoo on my stomach. It is the second symbol, Beth. This letter, on nights when the moon is full, gives me power over men whose mark is Gimmel, but it subordinates me to the men of Aleph, who on moonless nights owe obedience to those marked with Gimmel. In the half light of dawn, in a cellar, I have cut the jugular vein of sacred bulls before a black stone. During a lunar year I have been declared invisible. I shouted and they did not answer me; I stole bread and they did not behead me. I have known what the Greeks do not know, incertitude. In a bronze chamber, before the silent handkerchief of the strangler, hope has been faithful to me, as has panic in the river of pleasure. Heraclides Ponticus tells with amazement that Pythagoras remembered having been Pyrrhus and before that Euphorbus and before that some other mortal. In order to remember similar vicissitudes I do not need to have recourse to death or even to deception.

I owe this almost atrocious variety to an institution which other republics do not know or which operates in them in an imperfect and secret manner: the lottery. I have not looked into its history; I know that the wise men cannot agree. I know of its powerful purposes what a man who is not versed in astrology can know about the moon. I come from a dizzy land where the lottery is the basis of reality. Until today I have thought as little about it as I have about the conduct of indecipherable divinities or about my heart. Now, far from Babylon and its beloved customs, I think with a certain amount of amazement about the lottery and about the blasphemous conjectures which veiled men murmur in the twilight.

My father used to say that formerly – a matter of centuries, of years? – the lottery in Babylon was a game of plebeian character. He recounted (I don’t know whether rightly) that barbers sold, in exchange for copper coins, squares of bone or of parchment adorned with symbols. In broad daylight a drawing took place. Those who won received silver coins without any other test of luck. The system was elementary, as you can see.

Naturally these ‘lotteries’ failed. Their moral virtue was nil. They were not directed at all of man’s faculties, but only at hope. In the face of public indifference, the merchants who founded these venal lotteries began to lose money. Someone tried a reform: The interpolation of a few unfavourable tickets in the list of favourable numbers. By means of this reform, the buyers of numbered squares ran the double risk of winning a sum and of paying a fine that could be considerable. This slight danger (for every thirty favourable numbers there was one unlucky one) awoke, as is natural, the interest of the public. The Babylonians threw themselves into the game. Those who did not acquire chances were considered pusillanimous, cowardly. In time, that justified disdain was doubled. Those who did not play were scorned, but also the losers who paid the fine were scorned. The Company (as it came to be known then) had to take care of the winners, who could not cash in their prizes if almost the total amount of the fines was unpaid. It started a lawsuit against the losers. The judge condemned them to pay the original fine and costs or spend several days in jail. All chose jail in order to defraud the Company. The bravado of a few is the source of the omnipotence of the Company and of its metaphysical and ecclesiastical power.

A little while afterwards the lottery lists omitted the amounts of fines and limited themselves to publishing the days of imprisonment that each unfavourable number indicated. That laconic spirit, almost unnoticed at the time, was of capital importance. It was the first appearance in the lottery of nonmonetary elements. The success was tremendous. Urged by the clientele, the Company was obliged to increase the unfavourable numbers.

Everyone knows that the people of Babylon are fond of logic and even of symmetry. It was illogical for the lucky numbers to he computed in round coins and the unlucky ones in days and nights of imprisonment. Some moralists reasoned that the possession of money does not always determine happiness and that other forms of happiness are perhaps more direct.

Another concern swept the quarters of the poorer classes. The members of the college of priests multiplied their stakes and enjoyed all the vicissitudes of terror and hope; the poor (with reasonable or unavoidable envy) knew that they were excluded from that notoriously delicious rhythm. The just desire that all, rich and poor, should participate equally in the lottery, inspired an indignant agitation, the memory of which the years have not erased Some obstinate people did not understand (or pretended not to understand) that it was a question of a new order, of a necessary historical stage. A slave stole a crimson ticket, which in the drawing credited him with the burning of his tongue. The legal code fixed that same penalty for the one who stole a ticket. Some Babylonians argued that he deserved the burning irons in his status of a thief; others, generously, that the executioner should apply it to him because chance had determined it that way. There were disturbances, there were lamentable drawings of blood, but the masses of Babylon finally imposed their will against the opposition of the rich. The people achieved amply its generous purposes. In the first place, it caused the Company to accept total power. (That unification was necessary, given the vastness and complexity of the new operations.) In the second place, it made the lottery secret, free and general. The mercenary sale of chances was abolished. Once initiated in the mysteries of Baal, every free man automatically participated in the sacred drawings, which took place in the labyrinths of the god every sixty nights and which determined his destiny until the next drawing. The consequences were incalculable. A fortunate play could bring about his promotion to the council of wise men or the imprisonment of an enemy (public or private) or finding, in the peaceful darkness of his room, the woman who begins to excite him and whom he never expected to see again. A bad play: mutilation, different kinds of infamy, death. At times one single fact – the vulgar murder of C, the mysterious apotheosis of B – was the happy solution of thirty or forty drawings. To combine the plays was difficult, but one must remember that the individuals of the Company were (and are) omnipotent and astute. In many cases the knowledge that certain happinesses were the simple product of chance would have diminished their virtue. To avoid that obstacle, the agents of the Company made use of the power of suggestion and magic. Their steps, their manoeuvrings, were secret. To find out about the intimate hopes and terrors of each individual, they had astrologists and spies. There were certain stone lions, there was a sacred latrine called Qaphqa, there were fissures in a dusty aqueduct which, according to general opinion, led to the Company; malignant or benevolent persons deposited information in these places. An alphabetical file collected these items of varying truthfulness.

Incredibly, there were complaints. The Company, with its usual discretion, did not answer directly. It preferred to scrawl in the rubbish of a mask factory a brief statement which now figures in the sacred scriptures. This doctrinal item observed that the lottery is an interpolation of chance in the order of the world and that to accept errors is not to contradict chance: it is to corroborate it. It likewise observed that those lions and that sacred receptacle, although not disavowed by the Company (which did not abandon the right to consult them), functioned without official guarantee.

This declaration pacified the public’s restlessness. It also produced other effects, perhaps unforeseen by its writer. It deeply modified the spirit and the operations of the Company. I don’t have much time left; they tell us that the ship is about to weigh anchor. But I shall try to explain it.

However unlikely it might seem, no one had tried out before then a general theory of chance. Babylonians are not very speculative. They revere the judgements of fate, they deliver to them their lives, their hopes, their panic, but it does not occur to them to investigate fate’s labyrinthine laws nor the gyratory spheres which reveal it. Nevertheless, the unofficial declaration that I have mentioned inspired many discussions of judicialmathematical character. From some one of them the following conjecture was born: If the lottery is an intensification of chance, a periodical infusion of chaos in the cosmos, would it not be right for chance to intervene in all stages of the drawing and not in one alone? Is it not ridiculous for chance to dictate someone’s death and have the circumstances of that death sec recy, publicity, the fixed time of an hour or a century – not subject to chance? These just scruples finally caused a considerable reform, whose complexities (aggravated by centuries’ practice) only a few specialists understand, but which I shall try to summarize, at least in a symbolic way.

Let us imagine a first drawing, which decrees the death of a man. For its fulfilment one proceeds to another drawing, which proposes (Iet us say) nine possible executors. Of these executors, four can initiate a third drawing which will tell the name of the executioner, two can replace the adverse order with a fortunate one (finding a treasure, let us say), another will intensify the death penalty (that is, will make it infamous or enrich it with tortures), others can refuse to fulfil it. This is the symbolic scheme. In reality the number of drawings is infinite. No decision is final, all branch into others. Ignorant people suppose that infinite drawings require an infinite time; actually it is sufficient for time to be infinitely subdivisible, as the famous parable of the contest with the tortoise teaches. This infinity harmonizes admirably with the sinuous numbers of Chance and with the Celestial Archetype of the Lottery, which the Platonists adore. Some warped echo of our rites seems to have resounded on the Tiber: Ellus Lampridius, in the Life of Antoninus Heliogabalus, tell that this emperor wrote on shells the lots that were destined for his guests, so that one received ten pounds of gold and another ten flies, ten dormice, ten bears. It is permissible to recall the Heliogabalus was brought up in Asia Minor, among the priests of the eponymous god.

There are also impersonal drawings, with an indefinite purpose. One decrees that a sapphire of Taprobana be thrown into the waters of the Euphrates; another, that a bird be released from the roof of a tower; another, that each century there be withdrawn (or added) a grain of sand from the innumerable ones on the beach. The consequences are, at times, terrible.

Under the beneficient influence of the Company, our customs are saturated with chance. The buyer of a dozen amphoras of Damascene wine will not be surprised if one of them contains a talisman or a snake. The scribe who writes a contract almost never fails to introduce some erroneous information. I myself, in this hasty declaration, have falsified some splendour, some atrocity. Perhaps, also, some mysterious monotony … Our historians, who are the most penetrating on the globe, have invented a method to correct chance. It is well known that the operations of this method are (in general) reliable, although, naturally, they are not divulged without some portion of deceit. Furthermore, there is nothing so contaminated with fiction as the history of the Company. A palaeographic document, exhumed in a temple, can be the result of yesterday’s lottery or of an ageold lottery. No book is published without some discrepancy in each one of the copies. Scribes take a secret oath to omit, to interpolate, to change. The indirect lie is also cultivated.

The Company, with divine modesty, avoids all publicity. Its agents, as is natural, are secret. The orders which it issues continually (perhaps incessantly) do not differ from those lavished by impostors. Moreover, who can brag about being a more impostor? The drunkard who improvises an absurd order. the dreamer who awakens suddenly and strangles the woman who sleeps at his side, do they not execute, perhaps, a secret decision of the Company? That silent functioning, comparable to God’s, gives rise to all sorts of conjectures. One abominably insinuates that the Company has not existed for centuries; that the sacred disorder of our lives is purely hereditary, traditional. Another judges it eternal and teaches that it will last until the last night, when the last god annihilates the world. Another declares that the Company is omnipotent, but that it only has influence in tiny things in a bird’s call, in the shadings of rust and of dust, in the half dreams of dawn. Another, in the words of masked heresiarchs, that it has never existed and will not exist. Another, no less vile, reasons that it is indifferent to affirm or deny the reality of the shadowy corporation, because Babylon is nothing else than an infinite game of chance.

Translated by John M. Fein

Borges, Jorges Luis, “Labyrinths”, Penguin Books, Middlesex, England, 1987

Report On The Shadow Industry

From “Collected Stories“, 1994, University of Queensland Press.

Reproduced without permission

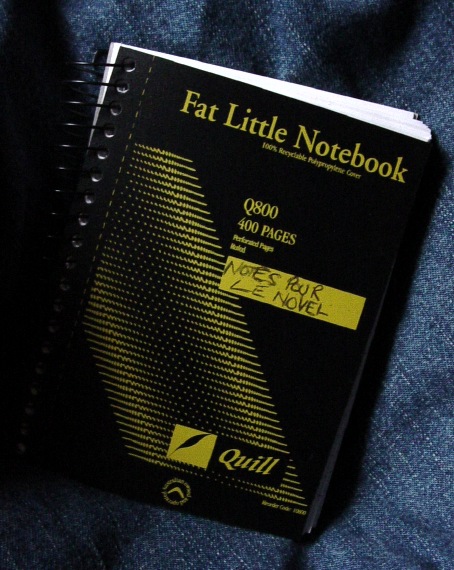

NaNoWriMo

So yeah, I’m going to do NaNoWriMo this year. I’ve taken this decision now so I’ll have lots of time to prepare, and flagging it here so it’ll be harder to back out when November rolls around.

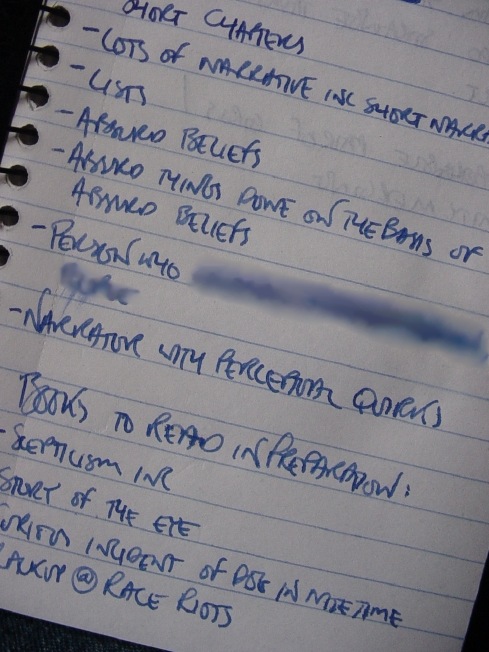

I bought this notebook to put thoughts and ideas in.

Because I’m a sucker, I’m going to acquire & read Chris Baty‘s NaNoWriMo bible No Plot? No Problem! I like the title.

It’s also a good excuse to re-read a few favourite books.

(138 pages of The Magus to go, weary sigh.)

Another preparatory project will be salvaging old writings dating back to the early 90s from my old Mac Classic II (pictured below), currently awaiting carriage to these people, who are going to put its 40MB hard disk onto a CD for me.

Poker Without Cards

I had an email out of the blue the other day from memeticist Howard Campbell – not the one from Kurt Vonnegut‘s Mother Night, but the one from Ben Mack’s fairly astonishing “consciousness thriller” Poker Without Cards, which can – and should – be downloaded as a .pdf here, or purchased here.

You could also listen to Joseph Matheny interviewing Ben here (part 1) and here (part 2). And watch this video, The Pitch, Poker and The Public.

You really could.

He asked if I knew any reviewers. I could only point him to Elmo – but the two of them were already acquainted.

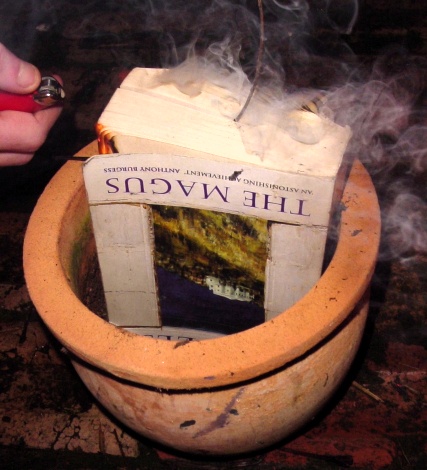

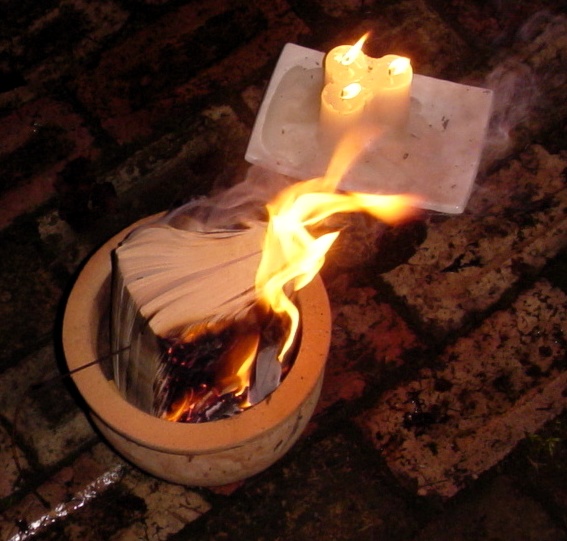

Magus Saga Continues, Etc

Well, the end of the month has arrived, but despite my resolution, I’m still 168 pages shy of completing The Magus.

I have been contemplating suicide, but it really wouldn’t suit my style and besides, I want to find out if the ending is really as ambiguous and unsatisfying as everyone says.

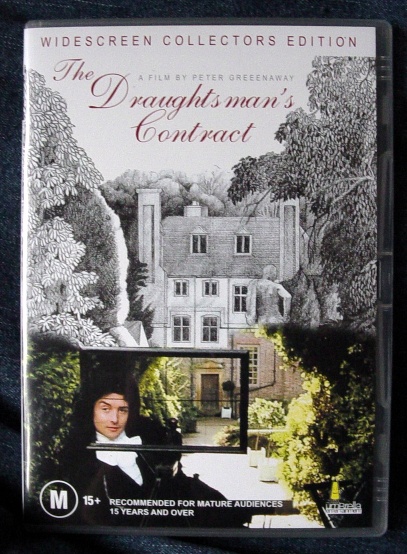

The DVD of A Zed & Two Noughts I was coveting here has gone, I discovered today. However in its place was one of PG‘s preceding feature, The Draughtsman’s Contract (pictured, below) – also with director’s commentary! Go the digital revolution etc. Feeling in need of a compelling reason to live some retail therapy, and wary of being gazumped again, I bought it.

Yay, DVD of The Draughtsman’s Contract with director’s commentary.

What else? I happened to pass pipe-smoking Bolte Bridge participant Operative Arachni on Barkly Street this morning. I smiled at her, but I don’t think she recognised me.

Here is a picture of someone else’s toaster (my own is too retiring for photos):

Brave New Wallet

In addition to buying clothes on Friday, I also got a new wallet. My old one was falling to pieces. Things were constantly falling out of it. I’ve lost four keycards in the last eight months or so because of this.

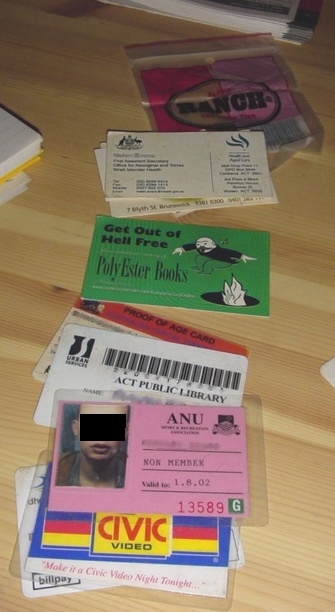

As the picture above illustrates, the new wallet is substantially smaller than the old one.

In many respects this is a good thing. However I had not entirely anticipated the extent to which the new one offers severely limited scope for one of my favourite passtimes, the obsessive collection and hoarding of random stupid crap.

My old wallet used give house room to all manner of daft accumulata. Unfortunately for the shiny novelty value of this post, I actually already partially cleaned it out when I moved. It was becoming unweildy.

Effecting the transfer nevertheless necessitated further wallet-crap cullage, and was a welcome excuse to indulge in a spot of the old ultra short term nostalgia.

From top down: plastic bag no doubt used for illicit purposes, business cards, handy Polyester Books “Get Out of Hell Free” card, old Canberran ID & membership cards, including ANU Health Club card, expiration date August 2002

Inscribed scraps of sentimental value

Tickets for things, mostly movies. I decided to retain the ones from Melbourne and archive the ones from Canberra, which comprised the bulk of the collection (note yellowing ticket to Kill Bill Vol 1, dated 27th October 2003, in foreground)

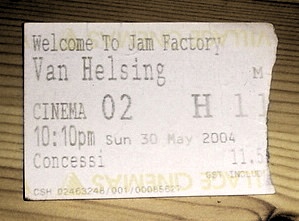

I was unsure what to do with this particular ticket, for a 10:10pm session of Van Helsing on Monday the 30th of May 2004, at the Jam Factory Village (see previous post), which I foolishly went to see entirely on the basis that Kate Beckinsale was in it.

It is an unhappy ticket; I associate it with sitting sadly on the floor of T’s flat in Toorak, realising that my first attempt to move to Melbourne was doomed. And despite the movie was absolutely dire.

But in the end I decided to retain it.

248 pages of The Magus left.

Things They Made Us Do At My Group Interview At The Jam Factory Village Yesterday

- All fifteen or so applicants were left to wait awkwardly around silently eyeing each other up for over 25 fun-filled minutes.

- We were given bingo-style cards with boxes containing phrases like “Has a sister”, “Plays a musical instrument” “Is currently reading a novel”, “Plays sport competitively” etc, and instructed to mingle and aquire signiatures from six fellow applicants in boxes whose phrases applied to them.

- Each of us had to stand up and tell the assembled company what our favourite movie was and why, what “our goal” was, and our most embarrassing moment. I was the only person who couldn’t think of a most embarrassing moment.

- We were given transcripts of three hypothetical staff-customer interaction scenarios, divided into groups of three and instructed to discuss how well or badly each situation was handled. One nominee from each group was then required to give a short statement of the group’s findings.

- We were given eight minutes in which to complete a short standardised maths test. I only finished about a third of it. So did the guy next to me, though.

- We were herded outside again and then called in three at a time to participate in two one-on-one roleplay exercises. These involved assimilating a sheet describing the two scenarios and some relevant information about protocols etc. I did everything right on a fuctional level but I kind of fucked up the presentation aspect of it, since by this point all I could think about was how badly I wanted the whole thing to be over.

I think the experience of participating in recent Neurocam group assignments was beneficial. The vibe of vague dread and menace engendered by the mysterious nature of the Cam was substituted with standard job-interview dread and menace, but in other respects it was an eerily similar kind of experience.

Unhappily, I miscalculated the number of pages of The Magus I had left to read. It was actually 300. Now it’s 274.

The Grumpy Post About The Magus

(There was a longer version of this but it’s kind of longwinded and tedious and I can’t be bothered to finish it – which is of course what happens when one attempts to read longwinded and tedious books which one can’t be bothered to finish – so I’ll just give you the gist:)

I want to finish The Magus. It’s really shitting me. I don’t like it at all. The concept is interesting but the execution is very contrived. The style is soporifically ponderous and all the characters grate my tits. The narrator, especially, is a pompous, self-absorbed pillock. He reminds so much of me; it’s terrible.

I want to read my Peter Greenaway book. And also, I’ve decided I’m going to do NaNoWriMo this year and have a pile of other books I want to read or reread in preparation. Like Georges Bataille‘s The Story of the Eye, which is great.

(Opens at random)

[Insert pyrotechnically surreal, lurid and obscene passage from The Story Of The Eye here.]

Let’s try it with the Magus.

*flip flip flip*

[Insert bromidically dreary, overdescriptive passage from The Magus here.]

See what I mean? [Well, probably not.]

I am going to finish it by the end of the month if it kills me, a possibility which cannot be discounted. I have 200 pages to go.

Filed under Books

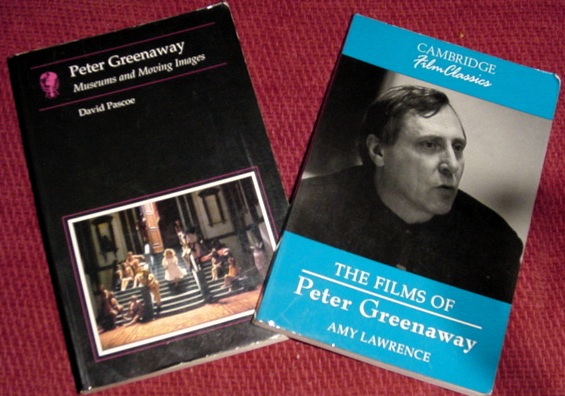

Greenaway

I often feel like I’ve been struck by lightning.

I want to watch Peter Greenaway‘s 1980 short Act of God again. It’s a documentary comprising a series of interviews with lightning strike victims. Lightning strike is recognisable as a phenomenon comparable to the mysterious Violent Unknown Event at the centre of Greenaway’s subsequent feature debut The Falls.

I originally saw both films about ten years ago, deep in the bowels of the National Library, where you could watch 16mm prints from the enormous film collection that they used to hold (which I believe now lives at Screensound) on quaint old Steenbeck viewing tables.

I was completely and totally obsessively in love with Greenaway’s work throughout my teenage years. It was the centre of my whole world. I want to get reaquainted with it.

I still possess dodgy VHS recordings (mostly taped off Eat Carpet over the years) of a number of his early shorts (H Is For House, Water Wrackets, Windows, Dear Phone and A Walk Through H), but not Act of God. And I’ve still never even seen Vertical Features Remake.

I really need to get these two DVDs.

I rescued these two books about PG from my parents sinking ship of a house:

Museums & Moving Images by David Pascoe and The Films of Peter Greenaway by Amy Lawrence

If I ever finish The Magus (I’m not going to give up on it now, but like others I’ve found it a tad bromidic) I’m going to read at least the Lawrence one again.*

And if I ever resolve my current deeply unsatisfactory employment situation, I’m going to celebrate by buying this DVD edition of A Zed & Two Noughts that I discovered at Chronicles on Fitzroy Street the other day, which features a director’s commentary track. My sixteen-year-old self would probably have keeled over dead with sheer excitement at such a prospect.

*Sidebar watchers will have noticed that I’m also currently reading Scepticism Inc by Bo Fowler – at work, since The Magus is a bit too bulky to fit comfortably in my pocket. It’s narrated by a sentient shopping trolley. It’s about a man who runs a metaphysical betting shop, which makes a killing because – metaphysical propositions being inherently unverifiable – it never ever has to pay out. These are just two of many great things about it.